One Man’s Reflection of Two Separate Great White Shark Attacks

It’s no secret that surfing comes with its lists of risks. From drowning, bacterial infections, reefs and rocks, jellyfish and stingrays, crazy locals, to random freak accidents, the list can go on and on… There’s even rogue dolphins who miscalculate their beautiful leaps onto the unsuspecting surfer. Ouch.

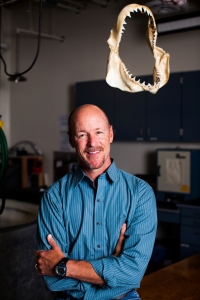

But none other than one of our most widely whispered topics, SHARKS, are more associated with the risks of being a surfer. Royce Fraley, a long-time surfer based in Occidental, California, is incredibly aware of this risk and has encountered our infamous grey suited landlord not once, but twice in the chilly Northern California waters.

“In both situations, it’s amazing how your brain kicks into a ‘fight or flight mode’ real quick,” said Fraley. “You automatically want to believe it’s not happening to you, but it is. All these thoughts happen within milliseconds.”

Like jelly to peanut butter, sharks and surfers go hand-in-hand by reputation, sans, well, let’s hope tastiness. In fact, based on my personal conversations, one of the most cited reasons why folks decide to not surf is because of our association with our oceanic toothy counterpart.

But consider statistics—for the average surfer who is in the water maybe not every day, but most days and is floating in the ocean for an extended period of time, what is the actual risk?

“No one plans to paddle out and hit a rock,” said Sean van Sommeron, Founder and Director of the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation in Santa Cruz, California. “Of course, every time you paddle out, you’re taking a risk. The statistics on shark attacks on surfers is very low on the list of possibilities. Surf board accidents are much higher on the list.”

Surfer Magazine did a lovely and realistic calculation for California surfer folks and concluded that California surfers have a 1-in-25,641 chance of being the victim of a fatal shark attack.

We’ve heard it all before—“you’re more likely to get struck by lightning.”

But sometimes lightning can strike twice for those special outliers, although they are few and very–VERY far between. For Fraley, who has logged more than 40 years of surfing around the world, charging double-overhead mysto reefs smack dab in Northern California’s “red triangle,” a little “brush” with our toothy landlords may be expected. However, for Fraley, not once, but twice did he pay rent and came out relatively physically unscathed.

No hesitation or barrel dodging–Royce Fraley charging in Northern California.

Photo: Scott VanCleepmut Photography

Northern California’s got a reputation among the salty-haired to mean two unpleasant things with one tempting caveat: cold and sharky…but lots of uncrowded spots! For Fraley, 10 is a crowd and spots are most often protected from wanton commercialization by thick blooded locals, that is if the break and pirate-like foggy coastline doesn’t scare you off first.

I got to know Fraley over the interwebs and he shared both stories of his attacks, which were covered by the SF Gate in 2006. More than 10 years has passed since his latest attack in 2006 and I was curious to see how he still manages to charge the crazy Northern California surf.

First Attack: September 1, 1998

A smallish surf day brought Fraley and a few of his good friends to surf Russian River, a spot located north of Bodega Bay, which is known for beautiful scenery, abundant wildlife and draining barrels. The trio were the only people in the water. Just as Fraley’s friends caught a few waves towards the inside, Fraley laid down on his board to rest from paddling along the sandbar.

Out of nowhere, he was launched around four-to-five feet into the air and disappeared into a giant burst of whitewater.

“If you took both palms of your hands and slam them on the hood of your car as hard as you can, that was the sound of this incredible impact,” said Fraley. “All I could see was whitewater all around me.”

Luckily, after that shocking launch, Fraley landed perfectly on his board in the water. The nose of the shark left a half-inch imprint on the bottom of Fraley’s board, even leaving behind a little skin.

“I think that shark was very surprised it hit something that was so damn hard, which was my fiberglass surfboard,” said Fraley. “That strike was like an ‘okay, I’m going in big time’ attack.”

After he landed, Fraley did not hesitate to paddle his 6’10” Campbell Brothers pintail towards the beach, his friends waiting on the sand, when he saw the water close to him swirl and watched as the shark drew up alongside him and chase him in.

“All I saw was the shark’s back and it’s dorsal fin,” said Fraley. “His dorsal was parallel to me and I was like ‘are you kidding me?!’ And before I knew it, I was in super shallow water and the shark just turned off.”

Once he reached the beach, Fraley collapsed while his friends quickly checked him for wounds. A little shaken, Fraley and his friends decided to conclude their session with much needed tequila shots and local Indian cuisine to celebrate his most interesting, rare and harrowing encounter.

“If you’re tracking the shark, it will be eyeing you, too and eventually it will take off,” said Dr. Chris Lowe, director of the California State University, Long Beach’s Shark Lab. “If you lose track of the shark, the first place you should look is behind you because that’s what a predator, like a shark, will do–they’ll move out of view.”

Dr. Lowe explained they often see this tactic while tagging great white sharks off of Southern California’s coastline. The smaller, more juvenile great whites are more easily scared off, however, the bigger guys and gals will often move off to the side and sneak up from behind. Dr. Lowe recommends that if a surfer loses track of a shark, to do a 10-second count and look behind. Sharks can identify an animal or person’s head and might often consider the surfboard’s nose as a person’s “head,” therefore recommends a surfer to also track with their board, too.

“If their prey know they can see them, there’s a chance that the predator won’t be able to take them down and may get hurt in the process,” said Dr. Lowe. “Your surfboard’s ‘head’ will make them sense they are being watched.”

Second Attack: December 10, 2006

Eight years had passed since Fraley’s Russian River encounter, and surfing was still on his to-do list. Fraley was itching for an evening session at Dillion Beach at a spot the locals like to coin as “the shark pit.” About 1,000 yards off the beach awaits a perfect and incredibly long A-frame peak that used to produce 3-500 yard rides in the 90’s. The spot is still filled with it’s fair share of big wave action as, according to Fraley, they will often see Mavericks crews and tow-in folks cruising the out-to-sea style lineup. If the location doesn’t make you flinch, then maybe a nice long paddle over the deep channel will.

“At this point, I had been surfing this spot for 15 years, had done this many times before,” said Fraley. ” It was a beautiful sunny December evening, right after a storm. A big set came through and I caught a couple of waves, which pushed me over into the channel.”

With the increasing swell, Fraley took his time getting back to the lineup, pacing himself for more waves. He rested on his brand new 7’6″ big wave board and as he was gliding over the channel, the water around him began to boil like a cauldron, the right side of his board lifted out of the water and Fraley rolled off the board.

“It was almost like the shark was a submarine surfacing,” said Fraley. “His bottom jaw hit the underside of my board and I started rolling off as the shark bit down.”

Fraley felt a sting in his right hip as the shark dove down with Fraley’s 10-foot big wave leash wrapped around it’s mouth. As Fraley instinctively grabbed ahold of his board for flotation, the shark dove even deeper beneath the surface with Fraley in tow. In the time spent below the surface, he experienced a gamut of emotions beginning with strong denial, anger and pain–to acceptance.

“There’s a part of me that accepted what was happening, I felt peaceful,” said Fraley. “Right when I felt that, I bumped off the side of the shark. It felt like someone pushed my whole right side up against a school bus.”

When Fraley reached the surface, incredibly shaken, he paddled towards a surfer, who immediately paddled away from him towards shore, and Fraley was left to make the long paddle on his own. A lifeguard, Brit Horne saw the commotion and quickly came to Fraley’s rescue where he found three imprints from the shark’s teeth on his right hip, which did not require stitches.

The University of California, Davis’ Bodega Marine Lab estimated the great white shark Fraley encountered to be about 15 feet long and weigh about 3,000 pounds.

“Not all bites may be predatory, sharks may be sending signals saying ‘you better back off,'” said Dr. Lowe. “Surfers often don’t even know the shark is in the area, and the shark hits and takes off. We just don’t know what the motivating factors are prior to those bites and it’s very rare that people actually witness those behaviors happening, so we have no context.”

Post-surf/attack session, instead of tequila shots and yummy food, Fraley was greeted with a barrage of news media at his front door when he got home. Even Good Morning, America! wanted an interview, but Fraley preferred to keep the news media’s often jarring sensationalism out of his evening and simply reflect on the greater lesson.

Reflection

Since his latest shark attack, Fraley has had time to contemplate his extremely rare attacks. Although from time-to-time, he understandably experiences a form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Fraley still manages charge big waves, but, seemingly remains more vigilant and paddles out with friends, on most days.

“The biggie for me was to actually go back out at the same spots,” said Fraley. “I had that need to be around other people and even now, I’ll be surfing any spot and sometimes I have a mini-panic attack, It’s almost like PTSD, but I usually tell myself to calm down and breathe and that definitely helps.”

Even still–it certainly hasn’t deterred him from charging full NorCal swells. In fact, he and a few friends will often search for lonely peaks along the less traveled areas of the north coast.

“Since the shark attacks, it really made me look at the way I carry myself and the way I am with others,” said Fraley. “The sharks taught me to get over myself, be humble, be considerate of others in and out of the water, to have a reverence for every moment you have, and to get over your own bullshit.”

Similar to how Native Americans often associated these experiences with predatory creatures, Fraley relates to this school of thought and sees both encounters as blessings.

“That’s how I have to look at my situation,” said Fraley. “It taught me to have a little bit more respect for yourself and life. It helped me realize how precious things are. So much of our society is ‘dog-eat-dog’ when we should be giving waves away, hooting someone into waves–bottom line: don’t be freakin’ selfish.”